The method by which we encounter new songs may have a greater impact upon our likelihood of adopting them than the contents of the songs themselves..

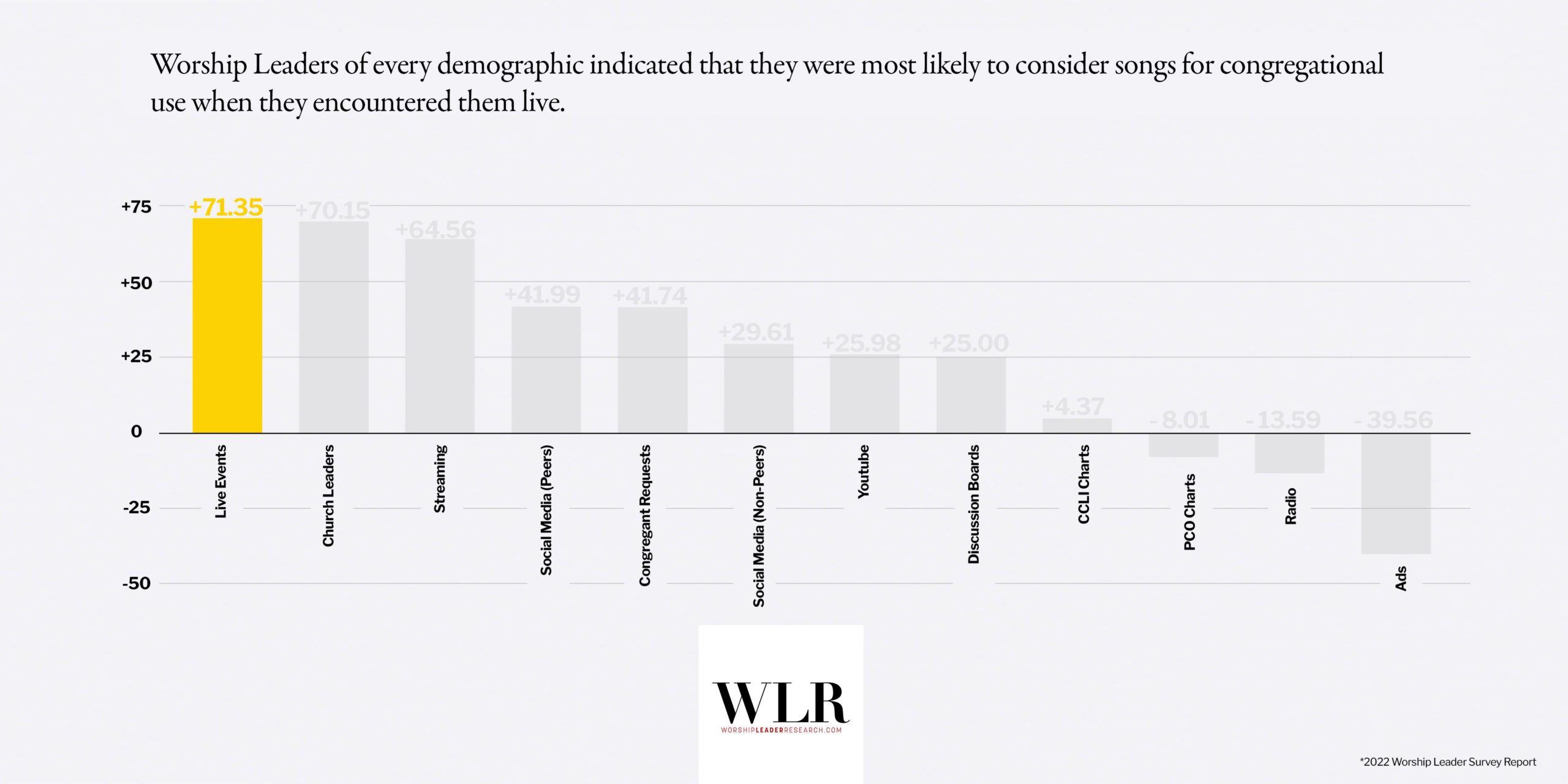

Over the past few articles, we have explored some of the most notable results from our 2022 survey of over 400 worship leaders. Our most recent article (which primarily looked at the complicated relationship between Worship Leaders and Christian radio) revealed that WLs find “live events and/or conferences” to be the likeliest source of new worship songs:

Survey respondents were asked to rate their likelihood of considering a song for congregational use when encountered through means like advertisements, charts, social media, radio, and others (many of which were rated quite lowly in terms of influence), but live events was the standout. In fact, according to the survey’s data explorer section on our website, every measured demographic of our survey respondents indicated that they were more likely than not to consider songs for congregational use when they encountered them live. One of our respondents remarked:

“The anomaly here [among this question’s choices] is the ‘live events and/or conferences’ source and here’s why – because it serves as a ‘lab/test market’ for me, both personally and corporately. Personally, it is in this context that I will actually sing through a new song. When I sing a new song, (which I typically don’t do by myself), I have found that my perception/evaluation of the song is much more ‘internalized/embodied’. It dramatically affects how I think and feel about both the musical and lyrical content of the song. There are songs which did not appeal to me as a passive listener that I deeply embraced once I became an active singer.”

Why might that be the case? This is the question we seek to explore in this article.

In an earlier article, we unpacked the results of another question in our survey (one that was, perhaps, a little more controversial). In the comments section for that question, a significant portion of people made remarks that indicated the text of a song was more likely to be a deciding factor in its adoption than other considerations:

“For [us], the most important aspect of song picking is picking songs that are in line with our beliefs…”

“I look more at theology and who it focuses on…”

“A song should be taken at lyrical value only…”

While it would be possible for some of these respondents to be primarily encountering new songs in ways that present the text of a song detached from its music, it is safe to assume that the majority of engagement opportunities involve a song as performed (holistically, music & text together, experienced sensorially). No other medium of discovery is likely to be more sensorial, though, than live events. Is it coincidental, then, that this medium also seems to be the most influential in persuading WLs that the songs encountered there are worth singing with their local congregations, regardless of how much value many of those same WLs claim to place upon lyrical content? As quoted above, singing through new songs can “dramatically” affect how we “think and feel about both the musical and lyrical content” of those songs, complicating the relationship between our rational and emotive choice-making.

Live events are often marketed and perceived as resourcing opportunities for local WLs. Popular worship conferences like Worship Together, Getty’s “Sing!”, or Passion play a curatorial role, helping WLs wade through the sheer volume of music coming their way, and hone their craft via workshops. But is the reason WLs are so likely to introduce the songs they encounter at these conferences based on perceived value, brand trust, or something more? Is there something about actively engaging with a song that has the potential to dramatically change the way we feel about that song?

Live events are often marketed and perceived as resourcing opportunities for local WLs. Popular worship conferences like Worship Together, Getty’s “Sing!”, or Passion play a curatorial role, helping WLs wade through the sheer volume of music coming their way, and hone their craft via workshops. But is the reason WLs are so likely to introduce the songs they encounter at these conferences based on perceived value, brand trust, or something more? Is there something about actively engaging with a song that has the potential to dramatically change the way we feel about that song?

One of sociology’s early giants (Emile Durkheim) coined the term “collective effervescence” to try to put language to some of the feelings people can experience when they join together in a religious ritual. When such groups communicate the same content in the same way at the same time (a phenomenon sometimes described as “ritual synchrony”) and do so in close proximity to one another, a certain energy is created and shared, leading participants to a degree of collective emotional excitement or euphoria. It would make sense that songs experienced in such an environment resonate differently with participants than songs experienced in less emotionally-loaded environments.

Over the last few years, neuroscience has started to both corroborate and explain Durkheim’s observations. Researchers have shown, for example, that group singing — even group singing of mediocre quality — generates a hormone known as Oxytocin, which helps to manage anxiety and stress and enhances feelings of social affiliation and trust within a particular social context. It would seem likely that these emotional states play a role in a singer’s feelings toward a song and its creators as their vehicle.

Obviously, not all live events are easily or accurately categorized as “religious ritual,” but as Dr. Kelsey Kramer McGinnis recently explored, the lines between the secular and the spiritual are not always easily drawn. Today, many critics of contemporary praise & worship cite this experience of collective effervescence as a reason

Emile Durkheim coined the phrase “Collective Effervescence”, describing the feelings associated with synchronous religious ritual, like singing.

to be suspicious of worship practices & song arrangements that can be seen as intentionally leaning into such phenomena or as “emotional manipulation”. While there may be merit to such critique, it’s worth remembering that this collective experience is neither new nor aesthetically limited. Diverse traditions across space and time have practiced communal singing, such that the songs employed are likely to participate in the dynamic process of both being a source of desire and an object of desire; they help us give voice to what we value, and (in turn) become something that we value.

Even if we could fully understand how our participation in live events makes us more partial to the songs shared together, that wouldn’t necessarily explain why WLs might feel more inclined to want to share those songs with their own congregations. “I prefer to experience the song myself in order to use it,” said one WL, while another remarked:

“I know that we are very much influenced by what we hear. If we hear it, there’s a good chance it may make its way into our playlists. Particularly live – wanting to bring the live experience and the emotions connected back to our local church.”

In the recently published A History Of Contemporary Praise & Worship, the authors systematically lay out how certain liturgical practices (the ones that have led to the worship style present in many modern, Western, protestant churches) spread virally throughout the 20th century’s latter half. This sometimes happened by stylistic evangelists going out and purposefully teaching these worship practices to others. Still, much of the time, it happened by soon-to-be-converts choosing to come to places where such worship was already happening (whether that was to a conference or a local church’s worship service). Not only did general worship styles spread this way, but also specific worship songs, since songs are often the most concrete & portable instantiations of the broader worship experience.

“Live events help me see how a song is executed and how it’s used and people respond to it,” noted one of our survey respondents. This ability to help WLs envision how a particular song can be led is part of the reason why early praise & worship albums were often recorded live rather than in the studio, a production choice that has carried on (through ebbs and flows) to today. What’s more, though live videos have long been an option as accompaniment for worship songs, the lessening cost of high-quality video production and the near ubiquity of video streaming services (with YouTube as king) have made these video accompaniments an expected norm. When churches or artists release new songs into the world, they often do so via video recordings that feature not only high-definition capture of the stage, but also handheld cameras that give the impression of movement and crowd-shots that show people energetically worshiping along with their voices and their bodies. As another of our survey respondents remarked:

“Live events help me see how a song is executed and how it’s used and people respond to it,” noted one of our survey respondents. This ability to help WLs envision how a particular song can be led is part of the reason why early praise & worship albums were often recorded live rather than in the studio, a production choice that has carried on (through ebbs and flows) to today. What’s more, though live videos have long been an option as accompaniment for worship songs, the lessening cost of high-quality video production and the near ubiquity of video streaming services (with YouTube as king) have made these video accompaniments an expected norm. When churches or artists release new songs into the world, they often do so via video recordings that feature not only high-definition capture of the stage, but also handheld cameras that give the impression of movement and crowd-shots that show people energetically worshiping along with their voices and their bodies. As another of our survey respondents remarked:

“…it is in this [live] context that I can gauge the collective sense of people’s ‘engagement’ with the song. That is a compelling variable/factor in my evaluation of new songs.”

These videos emphasize the importance that people place on experiencing a song and seeing other’s experience of that song, together. They likely have a similar (if not weaker) affective impact as being at the live events themselves, giving their viewers at least the impression of immersion in or participation with the songs. It may go without saying that the quality of these recordings is tied to the degree of their impact. The online church explosion of 2020 may be all the proof needed. All things being relationally equal, a one-camera shot of a person leading a song on an out-of-tune piano cannot hope to captivate worshippers like the output from those like the “Big 4.”

To what degree are people or organizations intentionally employing conferences and live events for song dissemination, whether expressly or covertly? Larger live worship events (such as conferences) often reflect commercial interests, rather than merely serving as neutral environments for worship songs. For instance, WorshipTogether (a trademark of Capitol Christian Music Group, a UMG subsidiary) started as an online platform to promote their song catalog. Its live conference naturally serves a similar promotional purpose. This subsidiary’s activities indirectly fulfill obligations to UMG’s shareholders. Similarly, Getty’s Sing! Conferences and Passion Conferences often involve business arrangements, such as administrative or co-publishing services through Capitol Christian Music Group. The artists included on the event’s roster often have direct ties to the publishers connected to the event. While this commercial aspect doesn’t negate the genuine intentions towards resourcing local worship leaders, it adds a layer of complexity to their role and influence, and suggests that brand loyalty may play a meaningful role.

So, how aware ought local church WLs be of their own role in this process, not merely as those being formed but as those making choices that help form others? They may think, “I don’t attend big conferences myself, and I certainly don’t organize any.” While our survey question could be interpreted as referring to large produced events, the considerations discussed in this article could be just as applicable to local church conferences (like area-wide or denominational gatherings), group prayer nights being hosted in your community, or even the average church’s Sunday morning worship service. The types of affective experiences that WLs described as being powerful for them are the very kinds of experiences that they often intentionally design for their own congregants.

If the influence of affective live performances can potentially override WLs’ own guardrails (be they theological or aesthetic), how ought they be thinking about the types of live events they choose to engage with, or the types of media they consume? What’s more, with the knowledge of the stakes at play, how ought these same WLs be thinking about the responsibility of choosing songs for their own congregations to experience? Recalling what we already read from one of our survey respondents:

“There are songs which did not appeal to me as a passive listener that I deeply embraced once I became an active singer.”

Week in and week out, WLs help curate opportunities for worshippers to become active singers, and (in turn) to deeply embrace certain rhythms, melodies, and lyrics… and to be shaped in the process of that embrace.