How do worship leaders (WLs) feel about prominent Big 4 brands, and how does brand affiliation affect song selection? This question raises a largely undetected and unexplored tension between what Worship Leaders say they do when they select songs and what they may actually do. If this discrepancy between intention and reality exists, though, how do we detect it? What factors contribute to it, internally and in the market, and how might Worship Leaders be served by addressing it?

In Worship Leader Research (WLR)’s Phase 1 research, we established that the Big 4 church-affiliated music groups (i.e. Bethel, Elevation, Hillsong, and Passion) were responsible for the majority of the top 25 most popular songs in the 2010–2020 decade. We also identified a short list of individual artists (e.g. Chris Tomlin, Phil Wickham, Leeland) who supplemented as individual contributors to the top 25. Our Phase 2 survey expanded upon this research by surveying 412 worship leaders’ attitudes toward songs written by these primary contributors. What emerged was a complicated account of how brand affiliation and trust impact Worship Leader’s attitudes about the music they choose.

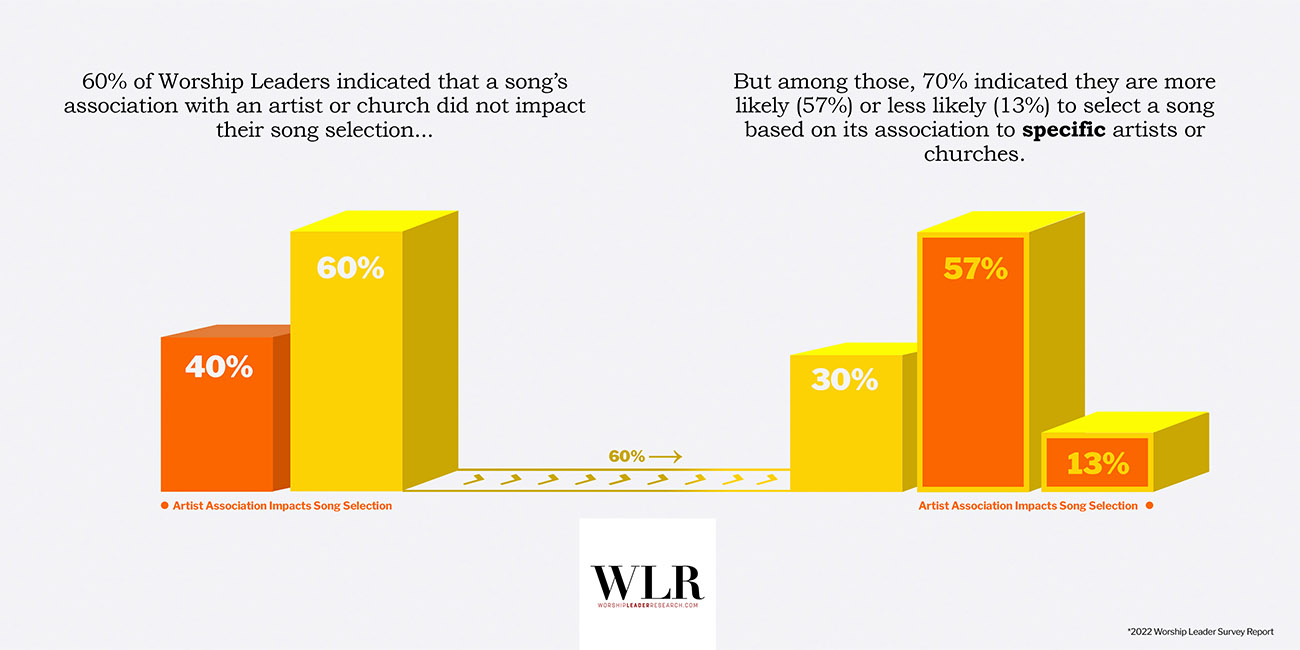

Among the six questions, WLR’s survey asked two questions about Worship leaders’ attitudes toward a song’s source or affiliation. First, we asked, “When considering a song for congregational use, how important is the song’s association (with an artist or church) to your decision on whether to use it?” Second, we asked, “How likely would you say you are to select a song for congregational use that is associated with… (inserted list of eight ‘primary contributors’ identified in Phase 1).” By design and intention, the first question was more general. The second question was more specific.

This article will present the survey results associated with these two questions about song association. Additionally, we will assess three broader themes and market forces that likely contribute to these attitudinal survey findings.

Part 1: Survey Results

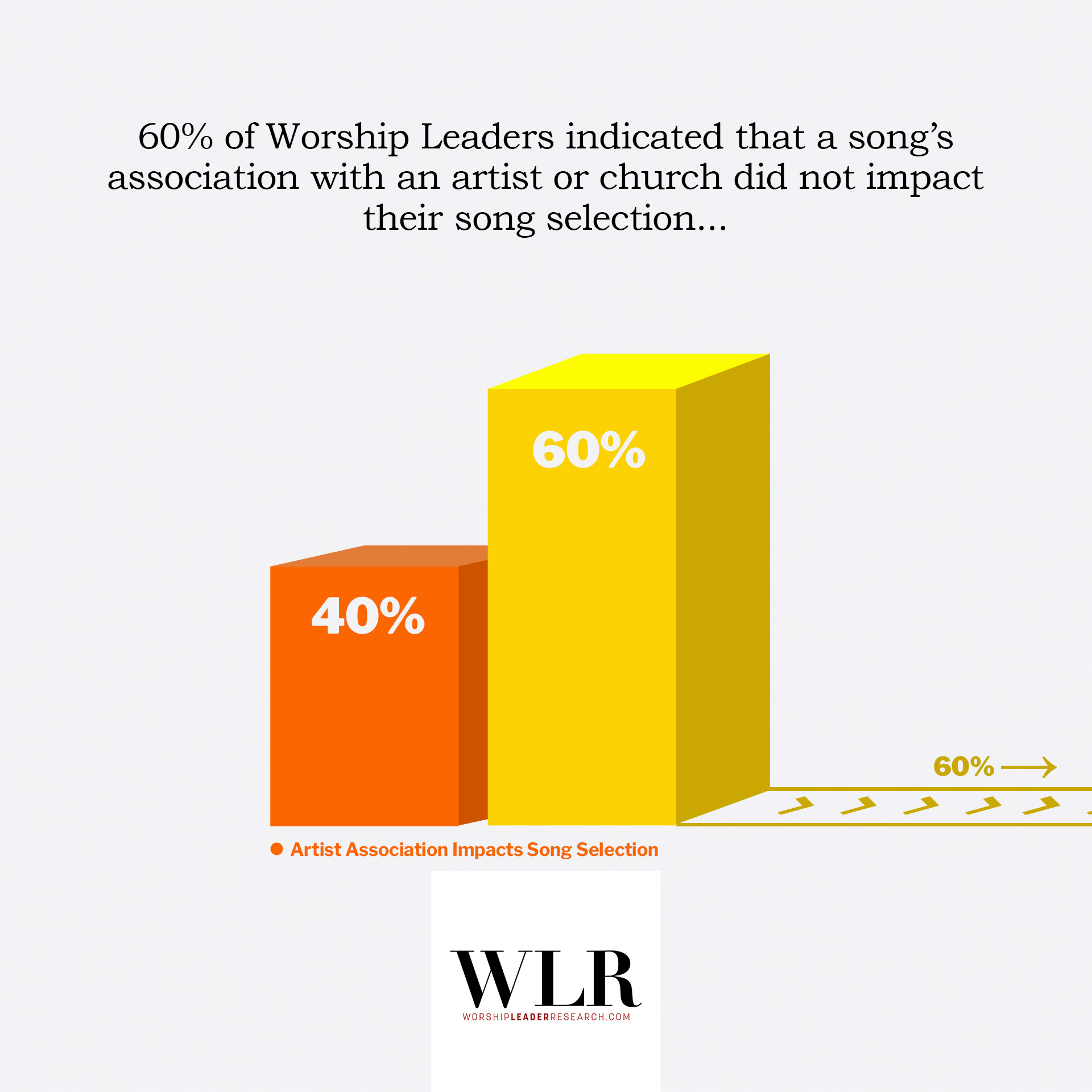

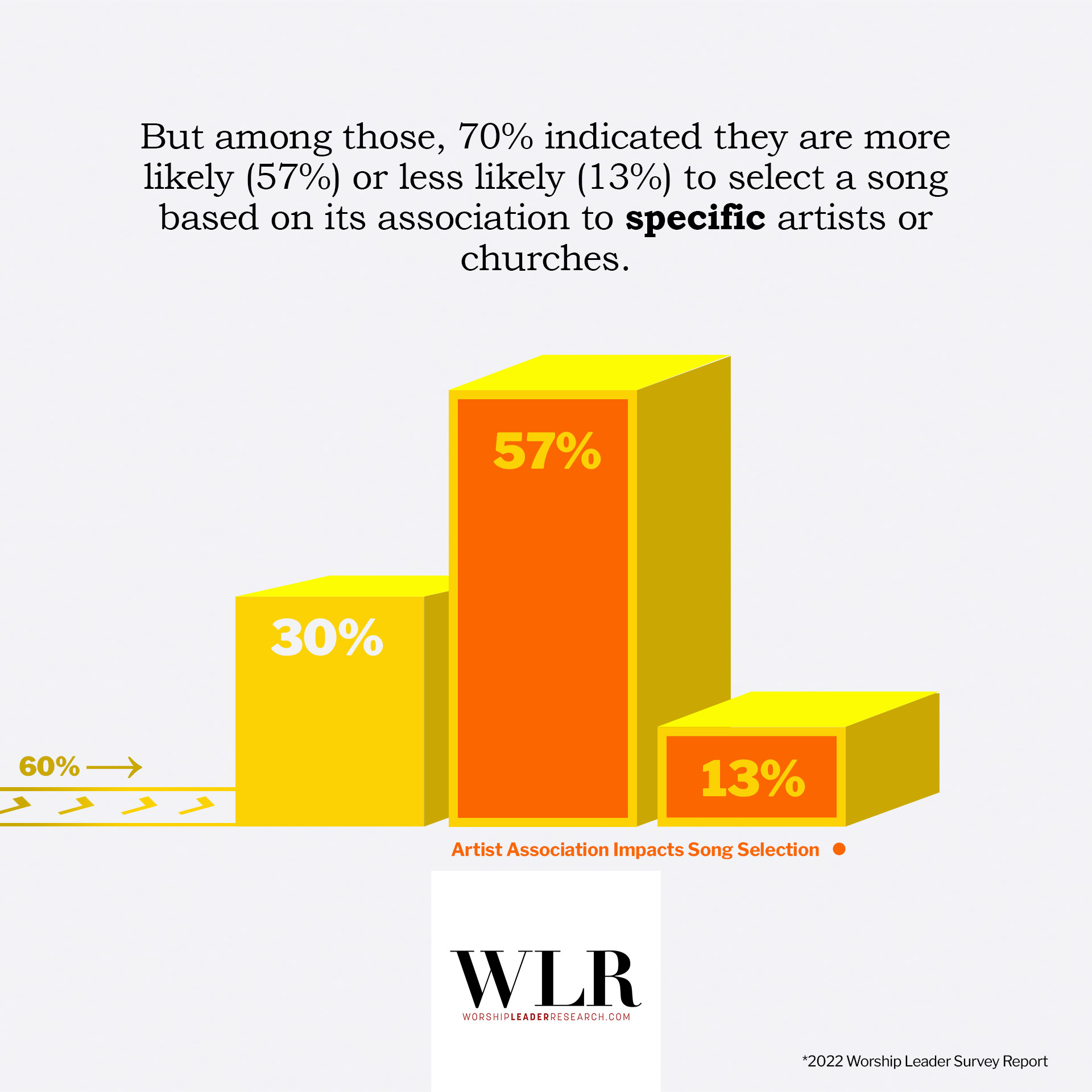

Our survey results on song selection and association revealed an intriguing inconsistency. 60% of Worship Leaders generally indicated that a song’s association with an artist or church did not significantly impact their song selection in survey question 2: 44% deeming it “unimportant,” while 16% were “indifferent.” Surprisingly, 70% of those who expressed indifference or deemed association unimportant shifted their stance when asked about specific artists in question 3. Specifically, 57% indicated that a specific artist association positively impacted the likelihood of selecting a song, and 13% reported a negative impact. This shift in sentiment underscores the nuanced relationship between song choice and artist association and suggests that general attitudes may not always translate to specific decision-making processes.

Overall, Worship Leaders communicated a notably stronger preference (and aversion) to specifically identified churches and artists while offering a more indifferent conviction about song association when the artists and churches were not identified. The received feedback in the comment boxes associated with these two survey questions provided great insight into this disparity.

Worship Leaders interpreted question two (on general association) and question three (on specific association) in different ways. Among the most common interpretations, many justified their survey response (about whether song affiliation was “important,” “indifferent,” or “not important”) by focusing on the “popularity” of an artist or church. Other Worship Leaders focused on “controversy” (i.e. theological or ethical) associated with an artist or church. We detected four common responses among the surveyed Worship Leaders.

- “WE USE LESSER KNOWN SONGS. WE AVOID BIG NAMES.” Many Worship Leaders who preferred selecting the songs of lesser-known artists (e.g. CityAlight, Charity Gayle, or a local church artist), indicated that artist affiliation was “unimportant” to them because they were not persuaded by the popularity of well-known artists or churches. For these Worship Leaders, primarily driven by the congregational fit of songs, popularity was not a high motivator for song choice. In fact, in some cases, a song source that was less “mainstream” was viewed as more favorable.

- “SOUND LYRICS ARE REALLY WHAT MATTER.” Some Worship Leaders, placing high value upon theological and biblical excellence, tended to view the song’s lyrical content as far more important to them than the sources from which it originated. In this, we saw a common recurring appeal: a song’s theological and lyrical content should stand on its own merit, regardless of the source. Some Worship Leaders not only indicated they should judge songs based on their content, but they further suggested this was the primary mechanism by which they do choose songs. Where the song came from was inconsequential.

- “IF THEY ARE DUBIOUS, WE AVOID THEM ALTOGETHER.” Other Worship Leaders indicated that affiliation was essential to their song selection. This was particularly true when artists or churches were perceived as being associated with questionable practices, theological heterodoxy, or publically reported ethical controversies. Worship Leaders holding this conviction commented that songs associated with these artists or churches, even if they were theologically or biblically solid, should be avoided at all costs.

- “IF IT PLAYS AND SINGS, IT IS GOOD.” Despite the common refrain that “Big 4 worship music all sounds the same,” some Worship leaders acknowledged that the musical quality and character of specific churches and artists were, indeed, contributing factors to their song selection. As will be addressed in a later article, some Worship Leaders admitted they wished their congregational worship experience was musically and aspirationally more like that of the Big 4.

It is clear that Worship Leaders responded to our two survey questions about song selection and association with different presuppositions, biases, and assumptions. When asked about the power of association generally in survey question two, Worship Leaders seemed more indifferent. However, the question of association struck a nerve when specific Big 4 churches and prominent artists were identified in survey question three and stronger opinions (both for and against church and artist associations) were detected.

Part 2 – Broader Themes

The survey results above indicate that while it is quite important for some Worship Leaders, song association is not explicitly or self-consciously the primary motivation for most Worship Leaders. However, a closer look at the survey data and comments reveals that affiliation with these artists and churches, as brands, has far more influence than Worship Leaders realize.

Brand Longevity

Consider, for example, the survey responses about selecting songs associated with Hillsong and Bethel. In recent years, Hillsong has received the most public scrutiny among the Big 4, for issues related to moral failings among their leadership. At the same time, Bethel has received criticism for their theological positions and faith practices on various issues. Among the Big 4, Worship Leaders reported that when selecting songs for congregational use, songs associated with Hillsong had the highest likelihood to be selected, and songs associated with Bethel had the lowest likelihood. How does this hold together? A variety of factors are likely in play.

Here, it is helpful to introduce the concept of “brand.” Popular worship groups operate as brands insofar as they participate in a marketplace where their name, alone, draws particular associations, especially regarding the quality of their product. Most Worship Leaders presumably accept this without question. Hillsong serves as a clear example of how they do so self-consciously. Leaders at Sydney Hills Christian Life Church rebranded the name of its church organization to Hillsong in the early 1990s as the popularity of its worship music began to grow. Three decades later, Hillsong possesses international recognition as a trusted brand in worship music.

Brand trust and longevity influence attitudes toward artist and church affiliation. While Bethel is affiliated with the greatest number of songs on the top 25 charts, Hillsong has produced and published music for almost two decades longer. Hillsong’s first major international worship music hit was produced in the mid-1990s when Integrity Music (at the height of its influence) began widely distributing Hillsong music. Around the same time, Bethel’s youth band, Jesus Culture, began releasing albums in the late 1990s (later spinning off into their own church and independent brand and label). Bethel’s first music release, distributed by EMI CMG, was their 2010 album, Here is Love, and included Jesus Culture artists. While a history of Bethel Church and Bethel Music is beyond this article’s scope, it suffices to say that Bethel, as it pertains to its music propagation and brand, is nearly 20 years younger than Hillsong.

Why is this important? To state the obvious, today’s Worship Leaders have engaged with nearly 30 years of widely accepted and endorsed Hillsong albums and releases. A whole generation of Worship Leaders has built an experiential trust in the Hillsong music brand, contributing to Hillsong’s strong, positive reception and continuing use by Worship Leaders.

The theological associations with these brands in particular are related to brand identity in general. Survey comments indicated that theological differences between a Worship Leader and a brand have a larger impact on song choice motivations than the ethical failings of leaders within a worship brand’s organization. Among many Worship Leaders, theology is assumed to directly impact song content. Ethical issues within a brand or organization tend to be considered distinct from the theological veracity of the brand’s songs. Nelson Cowan has explored this propensity in a recent article on “tainted brands.” He offers two common responses to a brand facing ethical controversies: (1) a “cease and desist” reaction. Churches stop offering financial support to the brand under review and terminate all ties and backing (e.g. royalties). Cowan reports that, curiously, very few Worship Leaders have called for this kind of response in light of the recent Hillsong documentaries. Neither has the industry curtailed available resources from Hillsong, even during the period of public and private litigation. A second response—more evident in our survey results above—is what Cowan calls (2) an “anti-Donatist” reaction. Accordingly, Worship Leaders allow a song to stand on its merit without bearing the scruples of the associated writer, music group, or popular worship leader. While “bad theology” in a song may be perceived as tainting a brand for Worship Leaders, the prevalence of personal, moral, and ethical failings is less likely to affect the reception of a song and its brand.

Song Merit and Social Proof

Worship Leaders overwhelmingly self-reported that theologically and biblically sound content is crucial in choosing a song. However, it seems difficult to argue that the songs appearing on the top of the charts are the most theologically rich of all songs available to Worship Leaders. It could be more accurately said that the chart-topping songs are theologically palatable to the broadest range of users. In a previous article, WLR suggested that promoting songs as singles is a primary mechanism by which the industry identifies (potentially) chart-topping songs. In an upcoming WLR article, we will confirm that Worship Leaders view peer endorsement and first-hand experiences with a song (e.g. via a conference) as the most powerful social forces in new song selection and its subsequent popularity.

Peer recommendations, gathered worship experiences, and song charts are all examples of social proof. When Worship Leaders are unsure of their choices, knowledge of their peers’ choices strongly influences them. This peculiarity drives social media enterprises, evidenced by, for example, viral video repostings, influencer endorsements, and peer product recommendations. Likewise, the charts—church-facing (e.g. CCLI) and listener-facing (e.g. Billboard or Spotify)—are examples of social proof. Though survey respondents report that CCLI charts do not play a significant part in finding new songs, a casual engagement with these charts, when looking for musical resources, undoubtedly does impact brand affiliation and user choice.

Resource suppliers like CCLI, PraiseCharts, and other streaming platforms play an active role in “organizing and programming the content they carry.” They act as facilitators in the relationship between the content creators and the broader industries in which this content is embedded. Platforms like CCLI and PraiseCharts are unique among charts in the broader music market. They provide a critical resource (i.e. copyright compliance and music performance materials) for Worship Leaders’ work. They are not simply conduits for finding new music. Instead, they act as “lagging indicators” of popularity. These charts serve as “match-makers” between producers and consumers. Through their function as royalty providers, they bridge the sophisticated interconnection between the labels, songwriters, Worship Leaders, church entities, and the pew-going worshiper. Because of this mediatorial role, charts are like other industry platforms and are “not neutral distributors, [but] they are also not inherently ‘powerful.’ Rather, power is an always unstable and shifting outcome of the ongoing attempt to coordinate between these markets.” While CCLI and PraiseCharts operate with different business structures, they rely on creating products that enable Worship Leaders to do their jobs more efficiently and quickly. But more so, the charts they publish are one product among the various others that offer a certain kind of social proof. The charts help Worship Leaders cut through the many available worship songs, help Worship Leaders identify popular songs their congregations may want to sing, and help Worship Leaders feel connected to the global church. Indeed, as Worship Leaders, we, too, have selected songs from the top 100 lists in hopes that it points to what songs a group of people might know. At the same time, the charts direct profitable traffic to their licensing and music performance resources.

While it is beyond the scope of WLR’s research to detail how these charts impact brand affiliation, we want to highlight that they have power. Empirical data suggests that charts have power in their curatorial choices. Additionally, the charts activate the power of social proof as a clear and direct effect on song chart position (assuming a song has met a baseline level of quality). In our research on single releases, we argued that the release of a song as a single was a prerequisite to chart success but not necessarily a firm predictor. In some cases, more than 50% of songs released as singles by the Big 4 did not appear on the top 25 chart. Industry gatekeepers, as market experts, cannot accurately predict which songs will ultimately appear on the charts. This is, in part, because the chart position of a song is unpredictable. Once a basic threshold of song quality is met, the infinitely complex world of brand affiliation, industry mechanisms, and social proof kicks in.

Cross-Market Brand Affiliations

The final element we want to explore is the various industry configurations that make brand affiliation a messy situation. While surveyed, Worship Leaders tend to link distinct associations to each artist, some songs and artists affiliate beyond their brand or label identity. Thus, there appears to be a spider-webbing effect within brand affiliation. Because songs can be associated with multiple artists or brands, Worship Leaders’ attitudes towards those brands do not always neatly apply to those brands.

Phil Wickham

For example, Bethel affiliates with multiple individual artists beyond their core collective. When they release a cover of a song written by Phil Wickham simultaneously with Wickham’s release of that same song, how is brand affiliation impacted? On the one hand, the songwriter or artist may get wider exposure to their music through affiliation. They may also risk positive or negative associations based on a Worship Leaders’ perception of this affiliation. However, for lesser-known artists or individual brands (like Wickham or Leeland), the collaboration undoubtedly increases visibility and revenue for their songs. Hillsong provides another example. Hillsong’s albums do not cover or feature songs from other artists or collectives, but Hillsong artists do collaborate for songwriting. They have also appeared on Passion albums because they have performed at the Passion Conference (related to but distinctive from the Passion/sixsteps label). How do Worship Leaders deal with these complex webs of affiliation?

Another element of industry configuration is important to note: the synergistic affiliation between music labels and the churches linked to them. Beyond their legal and financial structures, Worship Leaders brand associations intermingle the church and music group entities/identities. How does the reputation of a megachurch like Bethel lend credibility to its music label? For many, the “covering” or association with a church is one way theological orthodoxy is handled. The worship label is presumed to fall under the church leaders’ spiritual leadership and organizational hierarchy, regardless of the actual legal relationship. Indeed, the “success” of the megachurch—at least in terms of the sheer number of attendees, long cherished as a primary success indicator—may be part of the social proof or authentication of the spiritual value of the worship music.

On the flip side, how does the success of the music label lend credibility back to the church organization in a culture that has equated powerful and meaningful (even “anointed”) worship with the act of music-making? Indeed, what is a successful megachurch in the U.S. context that does not also produce its own worship music recordings? The popular megachurch branding model uses worship music as a central marketing tool and social proof of the church’s health and success. The effect is magnified at scale. To have a successful music label is to have a successful church, as we see with the Big 4.

Conclusion

Worship leaders approach the work of choosing songs with a great degree of thoughtfulness—they just disagree about what matters for song choice. We explored above how Worship Leaders place varying amounts of emphasize the theological rigor of lyrics, associations with artists/brands, and musical fit as they make choices for their congregations.

Beyond the work of making these discrete choices, Worship Leaders seem to underrate the power of a song’s association in general when compared to their attitudes toward artists or brands in particular. Better understanding the complexities of branded worship provides a way to explain this paradox. First, brand longevity influences long-term trust (e.g. Hillsong’s established loyalty in the market for over three decades). Second, social proof influences Worship Leaders’ attitudes in subtle ways that are difficult to quantify and recognize through sources like top-song charts. Finally, cross-market affiliations among artists challenge any sense of clean and neat brand associations—despite the confidence Worship Leaders impart on any one brand.

For some in the contemporary worship music world, market success is perceived as a sign of God’s blessing. It is important to continue examining how the industrial work of brand management, social proof through media marketing, and songwriting affiliations can have a tangible effect on what songs and artists become successful.