Introduction

We may not recognize it often, but the local Worship Leader might be a music industry powerhouse. You see, long before a chord rings out each and every Sunday, he or she chooses a humble set of songs—an offering if you will. But this “simple” choice extends beyond the church walls with a surprising impact on an industry worth hundreds of millions of dollars. In this article, we examine Worship Leader attitudes toward several key methods of new song discovery and the correlation between these local church setlists and the music industry at large.

Our initial research showed that the “Big 4” church-affiliated music brands (Bethel, Elevation, Hillsong, and Passion) were linked to almost all of the 25 most popular new songs released between 2010 and 2020. Building on this research, we surveyed 412 Worship Leaders in 2022 to better understand their attitudes toward various facets of the worship music industry. This included the brands most closely associated with these new songs and the vehicles through which they find new music. Our most recent October 2023 article, revealed that while Worship Leaders expressed a general indifference toward the idea of a brand’s association with a song, sentiments shifted when they encountered specific names. This suggests that brand longevity and social proof may have a more significant impact than Worship Leaders tend to recognize. Beyond branding, though, what industry machinations give these particular churches the upper hand?

In this article, we will present survey results from Question 6 of our survey, which pertained to Worship Leaders’ attitudes toward the various ways they might first discover new music. It will further explore how evolving technology has subsequently changed the Sunday service’s role in the music industry, for better or worse.

How Worship Leaders View New Song Sources

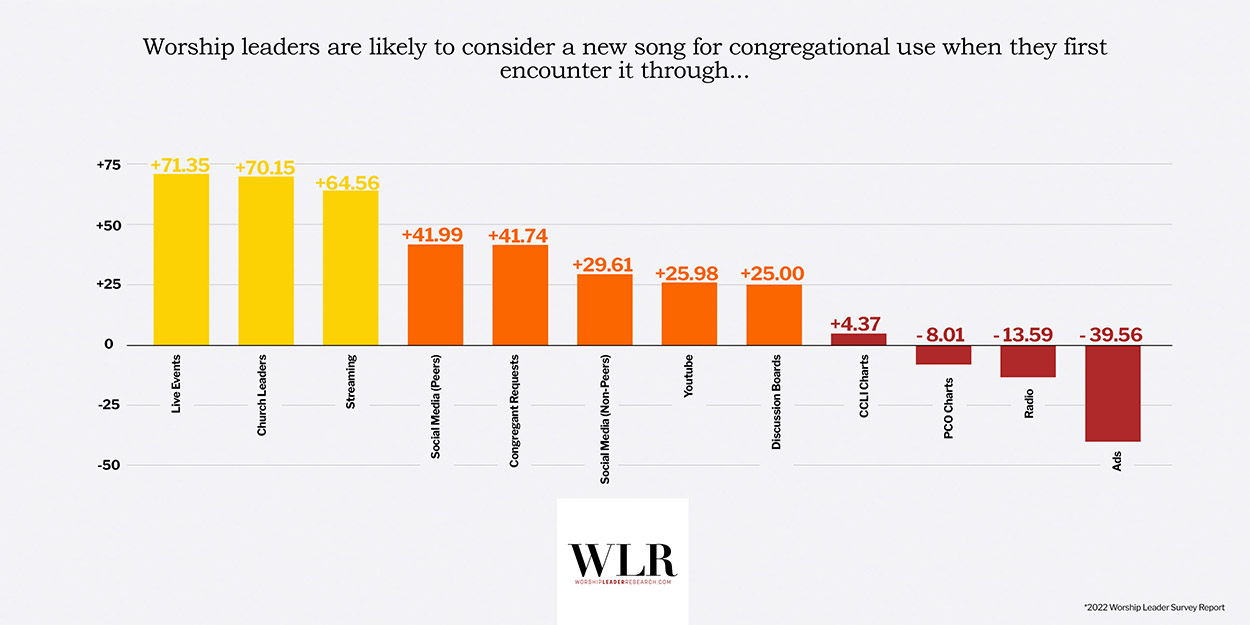

In our survey, we asked Worship Leaders how they perceived new songs for congregational use when first discovered through various popular methods. We asked them, “How likely are you to consider a new song for congregational use when you first encounter it through Live Events, ” Three distinct categories or groupings arise from their responses.

The first grouping, which includes live events, church leader requests, and streaming playlists, may be characterized by a visceral first-hand experience. When a new song is experienced in the context of a live event, it is likely to elicit heightened emotional responses. Hearing a streamed playlist song for the first time on a jog or in a car, for example, can evoke an emotional state. Lastly, given the power dynamics that exist in many church environments, a request from an authority figure, such as a lead pastor, can be received as having a unique emotional charge for Worship Leaders. As one surveyed Worship Leader commented, “Requests from Church Leaders…do we even have a choice?”

The middle grouping is, characteristically, social in nature and includes song recommendations from social media (peers), congregational requests, social media (non-peers), YouTube, and online discussion boards. These platforms for introducing new songs have built-in social proof—the concept that people tend to perceive the choices and behaviours of a larger group as correct— in common.

The final cluster contains the CCLI charts, Planning Center charts, Christian radio, and advertising. Each of these represents different facets of the commercial infrastructure around the music industry. The fact these are all among the lowest may suggest that Worship Leaders place more trust in vehicles perceived as more organic ones they can control. These survey results suggest Worship Leaders are at least mildly suspicious of openly commercial efforts as a source for new music.

An Unexpected Industry Gatekeeper

Why does any of this matter? What does this mean? Despite the sheer size of the Christian music industry, the attitudes of Worship Leaders toward new song-discovery methods matter more than we may realize. Although a local Worship Leader may presume their influence ends at their church’s front door, collectively, their song selections have implications far beyond familiar royalty platforms like CCLI. While one may presume that label staff, radio and playlist programmers, industry professionals, or even the artists themselves function as gatekeepers within the world of Christian music, it is the case that local Worship Leaders are often unexpected industry gatekeepers themselves.

Why does any of this matter? What does this mean? Despite the sheer size of the Christian music industry, the attitudes of Worship Leaders toward new song-discovery methods matter more than we may realize. Although a local Worship Leader may presume their influence ends at their church’s front door, collectively, their song selections have implications far beyond familiar royalty platforms like CCLI. While one may presume that label staff, radio and playlist programmers, industry professionals, or even the artists themselves function as gatekeepers within the world of Christian music, it is the case that local Worship Leaders are often unexpected industry gatekeepers themselves.

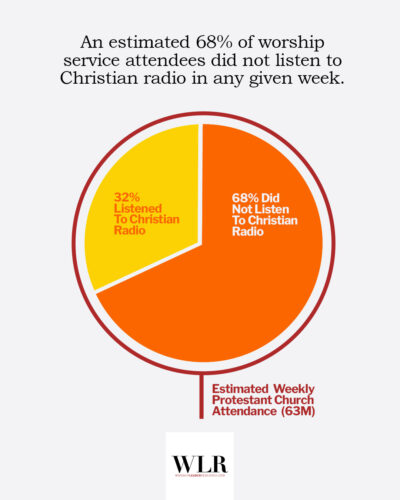

To illustrate this, let’s compare the public influence of Christian radio with that of local Protestant congregations. According to the Radio Advertising Bureau, around 20 million Americans listen to Christian or religious radio broadcasting, including talk and music radio. On the other hand, Pew Research reports that about 59 million Americans weekly attend Protestant religious services, while an additional 16 million attend services about once a month. This suggests approximately 63 million Americans attend their local Protestant church each Sunday.

Now, exact comparisons can be challenging. There’s no unanimous method for tracking, but according to industry insiders, a substantial number of those 20 million Christian radio listeners don’t regularly attend church. It is also true that many Protestant churches don’t adopt contemporary worship, though the number of those attending churches which incorporate some contemporary worship music has been growing exponentially for decades. Still, it remains clear that many more people attend Protestant churches without tuning into Christian radio than those who do. This suggests that the choices made by Worship Leaders in their song selections resonate with a broader audience and have a more profound impact on the Christian music landscape than previously recognized.

Although there are numerous nuances in how these datasets interact, including the style and format of those churches, it is clear that for many churchgoers, the Sunday service may be the primary way they learn of and grow to love new Christian music.

In a separate study, WLR team member Shannan Baker surveyed church congregants about their favorite worship songs. She found that over a third (37.25%) first encountered these songs during immersive live events, such as camps, conferences, concerts, or retreats. Notably, nearly 30% were introduced to these songs within the walls of their local church. In comparison, only 12.75% credited radio as their initial point of contact with their favorite worship music. This data underscores the pivotal role that local church services play in introducing and disseminating worship music, reflecting a significant shift away from traditional media platforms. Even if unintentional, this places Worship Leaders in a crucial role, connecting churchgoers to the broader Christian music industry. This is more true today than ever before.

First Exposure and the “Cold Start Problem”

Church attendees not well-versed in Christian music might find that a song played during worship is their gateway into a vast musical landscape. In a previous article, we showed that a change in how songs are distributed—namely, digital singles instead of albums—has dramatically impacted which songs become popular in the church setting.

Yet, with AI and machine learning’s expanding role in streaming services like Spotify, a person’s initial song choices within a genre can significantly affect the music later suggested to them. This stems from what tech experts call the “Cold Start Problem,” where an algorithm can’t offer relevant suggestions without enough data on a user’s tastes. So, when a worship song from a Sunday service is streamed on Spotify, it sets the stage for future music recommendations. Like a social media feed, Spotify’s algorithm inevitably relies on a popular technique known as “collaborative filtering,” which predicts what other songs might resonate based on what listeners within the genre have enjoyed.

Consider a churchgoer who hears a moving worship song but doesn’t usually listen to Christian radio. If they stream this new song on Spotify, the platform acts like a personalized DJ. While other factors are at play, the listening behavior of other users provides a valuable shortcut for the technology to personalize suggestions.

This fact brings us to what might be a trope for those familiar with the Christian music industry: the inescapable influence of a marketing persona known as “Becky.”

Becky’s Ripple Effect

Marketing personas are data-driven representations of a target audience that companies and industries use to better understand their buyers’ or listeners’ practical and emotional needs. “Becky” is an example of a persona commonly used by Christian radio stations nationwide. While “Becky” represents only 6% of the data we collected in our survey, her influence on Christian Music and worship music can’t be overstated.

Chris Hauser, a veteran music promoter, has played a crucial role in popularizing worship music on Christian radio. In an interview with one of our team members, Hauser explained that many Christian radio stations rely on Troy Research, a national research chart that collates information from a range of bigger stations. “Fifteen years ago,” says Hauser, “Becky was a 34-year-old mom with two kids in her minivan. Nowadays, it seems that 35-44-year-old females are buying Christian concert tickets, while 45-54-year-old females are keeping the lights on at non-profit stations. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, every Friday was like Christmas morning for me and other radio promoters, with stations adding 8-10 songs weekly. But the most played song on a radio station was heard for only twelve weeks before it was gone. The staff thought, ‘If we’re tired of it, everybody else probably is, too.’”

But subsequent research into Becky’s preferences changed all that.

“Programmers realized that when they grew tired of a song after twelve weeks, their primary listeners had only just figured out that they liked it. So they slowed down their rotations, taking the available slots from 8-10 per week to just 1, on average, for the past 20 years.”

Hauser suggests that today, 600-800 new songs are promoted to Christian radio per year, yet most stations are adding a maximum of 55 to 60. Some key stations are only adding 20 new songs each year. This makes the target audience, “Becky,” more critical than ever. In part, every song addition from a new artist has to convince a radio programmer to say “no” to one from an established artist. “After all,” says Hauser, “(Becky) doesn’t know what she likes—she likes what she knows.

“When a major station adds a song, the streaming in those markets increases exponentially within two weeks,” says Hauser. “Radio listeners hear a song and then find it.

“There have been times in the last ten years, especially as streaming has continued to grow, that we will pick a single to send to radio based on its streaming numbers. We can tell programmers that this new Elevation Worship song already has 50 million streams, and it’s this big at Planning Center and this big at CCLI. You’ll not be hurt by playing a song with 50 million streams because your listeners are already familiar with it.”

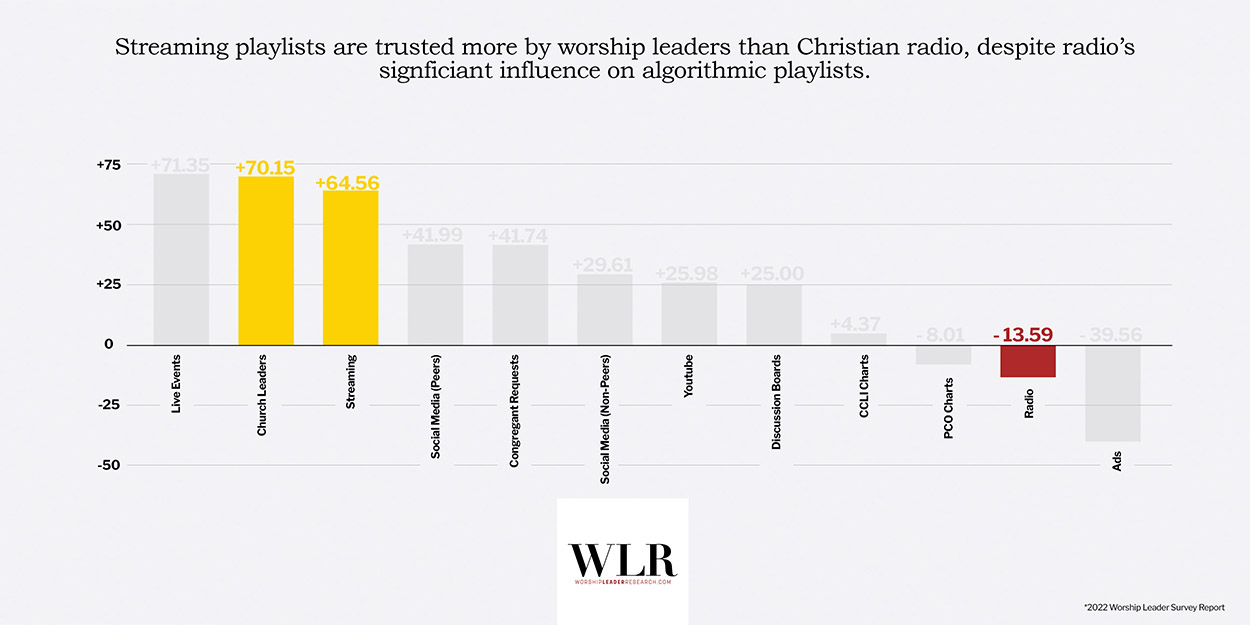

In our survey, Worship Leaders ranked Christian radio relatively low as a source for discovering new music for their congregations. Despite this, radio might still indirectly shape their choices. Although Worship Leaders might not consciously prioritize Christian radio, “Becky” may yet have her toe on the scales. This is because Christian & Gospel music—the commercial grouping to which worship music belongs—is often lumped together as one genre by the industry, and the algorithms that recommend music rely on this data.

However, a shift is underway that places Worship Leaders and many radio programmers at odds, thanks to a sister station of the nation’s largest radio network. KLOVE, owned by the Educational Media Foundation (EMF), has long been dominant in Christian music. In recent years, their sister station, Air1, has almost exclusively played worship music.

Hauser continues, “We’re now running up against some blockades, where other Christian radio stations say ‘I have a worship contingent,’ choose not to play more than 3 or 4 worship songs at any given time. They’ll say, ‘With Air1 in the market, we need to differentiate ourselves.’ We’re getting more pushback than ever around worship songs on the radio.”

With this in mind, Hauser believes that radio program directors and local Worship Leaders are in similar influential positions. They have limited time or space for new songs, and they need to choose songs they believe will land with their audience.

Even if many churchgoers or Worship Leaders don’t listen to Christian radio, Becky’s influence permeates through the sheer volume of data she provides to Spotify and other listening platforms. This connection between radio preferences and Sunday service song selection indirectly affects the overall song ecosystem and puts Worship Leaders and radio programmers in a dance that perhaps neither one chooses.

Trusting the Algorithm

The dance between radio and Sunday services is unavoidable in our internet age, partly because of a surprising response to our survey question: Worship Leaders weigh the influence of streaming playlists almost as highly as first-hand live experiences and specific song requests from church leadership. In a way, this makes sense. Streaming platforms play a vital role in the consumption and discovery of music. Platforms like Spotify have intentionally sought to consolidate those two experiences. In fact, in 2019, Spotify founder and CEO Daniel Ek boasted to investors that the popularity of Spotify playlists represents “a massive transformation” that “puts Spotify in control of the demand curve” (Spotify Investors, 2019) (p3). While these algorithm-driven platforms may appear to take center stage for Worship Leaders, what’s not often discussed is how the algorithms and industry structures behind these kinds of playlists can discretely amplify the influence of the radio market and the industry around it.

Editorial and algorithmic playlists stand out among various popular streaming platforms. Editorial playlists are assembled on each platform by a surprisingly small group of employees responsible for managing a specific genre or even multiple genres of music.

Algorithmic playlists are automatically generated based on user behavior through machine learning. In our survey, Worship Leaders indicated a burgeoning trust in these algorithmically curated playlists as well. One respondent shared, “I definitely get a lot of the ‘new’ songs by listening to a streaming service radio. Often, I’ll select an artist’s radio station on the platform and enter a discovery mode to see what I come across.”

It’s tempting to believe that machine learning algorithms simply present us with music that aligns with our tastes. This might hold true to some extent, but it’s important to consider the implications. As we’ve noted, these algorithms are not operating on neutral code—they’re influenced by the listening habits of millions of users. For instance, when a user—let’s call her ‘Becky’—streams her favorite worship song, which she originally heard on the radio, this data contributes to the recommendations made to other users. Consequently, when Worship Leaders turn to editorial and algorithmic playlists for new song ideas, it is ‘Becky’s listening patterns, along with those of countless others, that are likely shaping their discoveries.

Labels and larger distribution companies may also have an invisible upper hand regarding the few spaces in editorial playlists, which might help their new releases overcome the “Cold Start Problem.” For example, one popular Spotify playlist is “New Music Friday Christian.” Each week it highlights a mix of new and nearly new singles within the Christian & Gospel category. One former label streaming promoter, Dave Taylor, put it this way: “From what we can tell, if a song doesn’t make New Music Friday Christian, financially, it’s dead in the water.”

One survey commenter put it this way: “I listen, every Friday, to our churches release radar on Spotify, and Spotify’s new music Friday (Christian) playlist. That is primarily where I find new songs.”

This popular playlist features a mix of brand-new releases and those only a week or two old. There are only 100 available spots on this playlist. In the Christian & Gospel channels alone, editors for Spotify and Apple report getting upwards of 1,000 songs per week. For every slot on these coveted playlists, 10 or more won’t make the cut. Though platforms like Tunecore and others appear democratic, allowing artists to inexpensively distribute their music, they don’t solve the “Cold Start Problem” for smaller artists because of a different challenge: access.

For example, the official playlists at both Spotify and Apple are programmed by a surprisingly small group. In each case, 2 or 3 people program all official editorial Christian & Gospel music playlists. Knowing this, label and distribution representatives communicate regularly with these editors, often supplying a ranked list of their own label’s releases in a given week to maximize their commercial impact. One WLR team member, music artist Elias Dummer, has personally adjusted release dates on key singles to place better on these ranked lists, increasing the chances of editorial placement on “New Music Friday Christian.” Once back-channel requests like these are accounted for, it’s easy to imagine that little space or time remains for smaller independent artists.

Conclusion

The convergence of data, algorithms, and human preferences shapes the future of music discovery and consumption. The power of data-driven marketing is evident through singular personas like “Becky.” This might raise concerns about diversity and representation in the music presented to Worship Leaders and their congregations. As streaming platform strategies become more established, the tug-of-war between algorithmic recommendations and human curation becomes more pronounced. This leads to a further homogenization of content, potentially favoring established names and neglecting diversity.

The convergence of data, algorithms, and human preferences shapes the future of music discovery and consumption. The power of data-driven marketing is evident through singular personas like “Becky.” This might raise concerns about diversity and representation in the music presented to Worship Leaders and their congregations. As streaming platform strategies become more established, the tug-of-war between algorithmic recommendations and human curation becomes more pronounced. This leads to a further homogenization of content, potentially favoring established names and neglecting diversity.

In all this, it is essential for Worship Leaders to consider the broader ecosystem of worship music when selecting songs. Commercial interests and the interests of local churches may not align, but both would benefit from a thoughtful and transparent approach to discovering new music for congregational use. Furthermore, live events play a crucial role in introducing new songs to Worship Leaders, and the music industry may have a discreet influence over them, too. In a future article, we will examine this powerful dynamic in greater depth.