Wishful Worship: The role of aspiration in Sunday morning setlists

“Do you wish your church was more similar in worship culture/style to the churches and/or artists like The Big 4?”

In our survey of over 400 worship leaders (WLs), this question was posed regarding the influence of “culture” and “style” of worship on their church’s worship practices. (To find out who the “Big 4” are, check out this article on the “Big 4” brands.) This survey question was rooted in one of our initial hypotheses, namely that WLs’ preferences are shaped not just by the contents of the songs they lead but also by the broader contexts in which these songs are produced and performed. As we’ve discussed elsewhere, WLs often grapple with complex feelings about the origins of their chosen songs, including concerns about the theology, practices, or reputations of some of the prominent churches producing them. But what would these same WLs’ opinions be towards those churches if we were somehow able to specifically identify their “worship culture/style”?

Before we look at some of the data and comments from our respondents, it’s worth noting the potential ambiguity of the question itself. The terms worship “culture “and “style” encompass a wide array of meanings, reflecting everything from the communal and musical aspects of worship to an emphasis on creativity and songwriting within churches. This diverse interpretation of meanings is evident in the following survey responses:

“Similar in the culture that worship is something to do, not something to watch as it seems like it is sometimes in smaller churches that push against the worship industry culture.”

“Not necessarily a copy for copy’s sake, but a culture that’s excited to worship and celebrate Jesus.”

“I wish my art was encouraged in the church, in the way that the leadership of the aforementioned churches seems involved in the direction and creation of the art. I have been making music alone thus far.”

“In style, yes. In theology, absolutely not.”

“Not style necessarily, but the perceived or actual creative culture within larger churches is attractive.”

These comments shed light on the multifaceted relationship WLs have with the concepts of “culture” and “style,” illustrating a desire among WLs for more than mere musical alignment. For example, the terms “culture” and “style” may evoke an aspirational desire to share the perceived ethos of the congregations, the musical styles of the bands, or even the onus placed by the churches on creativity & songwriting. The term “culture” in particular might also have prompted respondents to consider group dynamics within prominent worship bands, such as their sense of camaraderie/community or musical excellence. Recently, the increased social media presence of these major worship brands has humanized and lionized these teams. Perhaps this entices “weekend warriors” to wish they were a part of these types of professional circles, as reflected in the following comments:

“…while maintaining congregational [engagement] in worship, it is a clear goal to become more and more musically polished and refined for the glory of God.”

“I do desire more participation from the congregation and dedication from team members.”

“I could do without the lights and fancy stage dressings. But I do admire the musicianship and team mentality of a lot of the mentioned artists.”

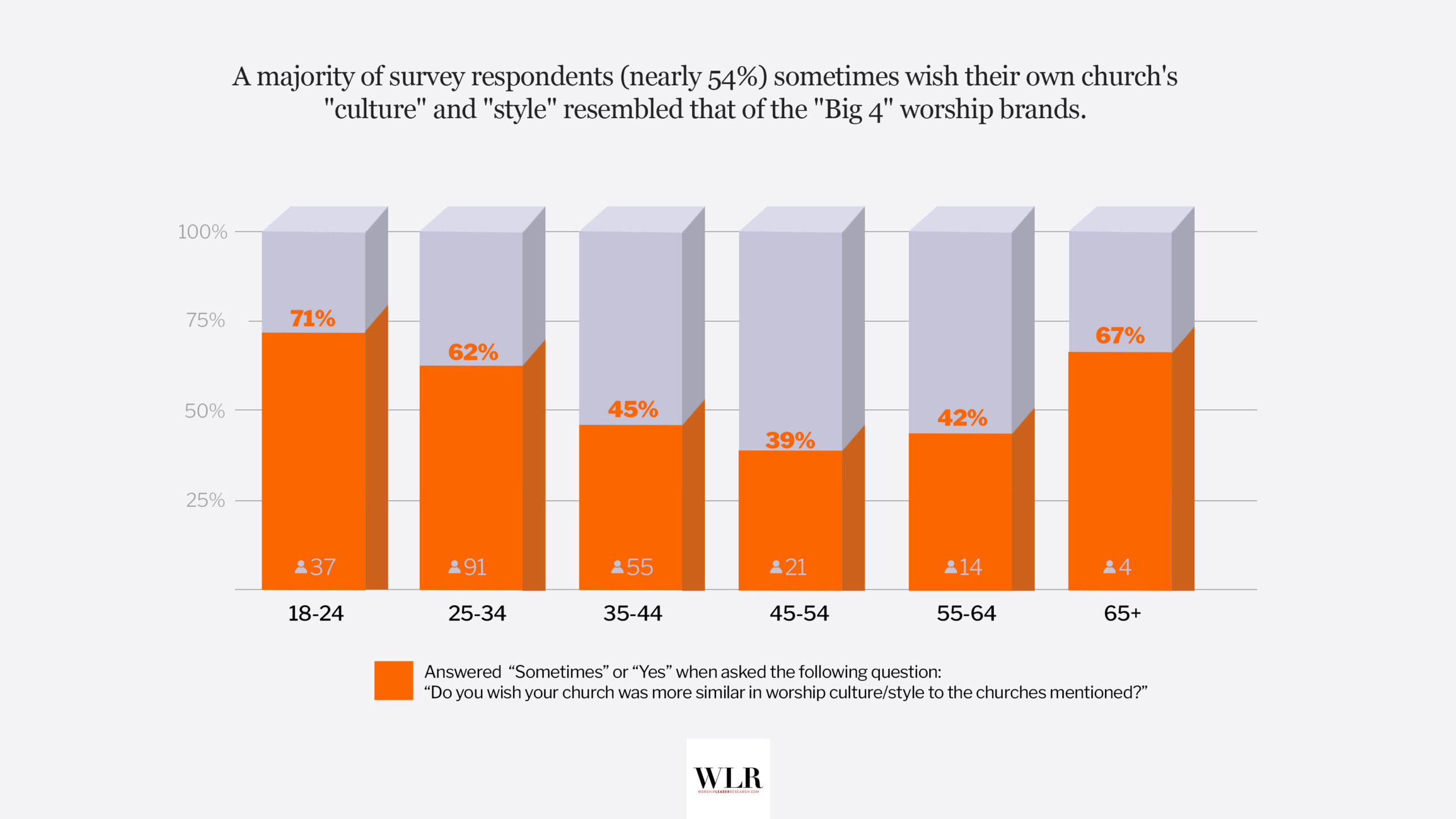

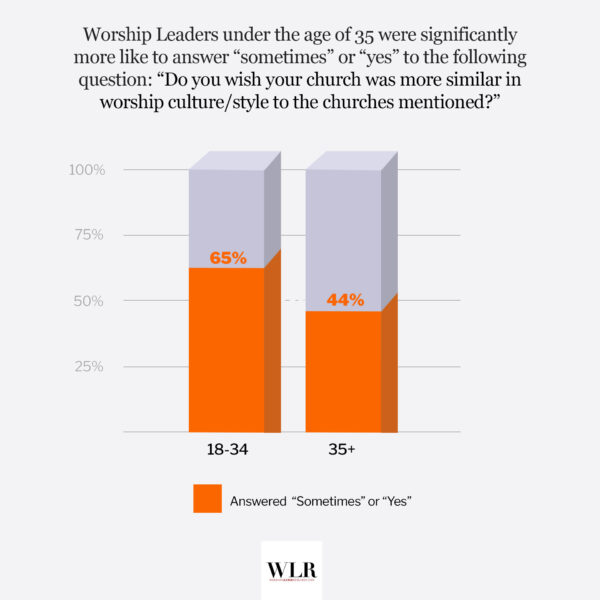

With that being said, the survey revealed that a majority of respondents (nearly 54%) sometimes wish their own church’s “culture” and “style” resembled that of the “Big 4” worship brands. Yet, an intriguing trend emerged when more closely examining the responses across different age groups:

Notably, Gen Xers (born 1965-1980) were least likely to respond positively. Why might this be the case? Is this due to their formative years coinciding with the rise of stadium worship events, like the first Passion Conference in 1997)? Does it have something to do with the kinds of churches these WLs are likely helming? While additional data would bring clarity, age clearly played a pivotal role in shaping responses to this survey question.

You might find these figures surprisingly high or low, or they might align exactly with your expectations. Regardless, one important data observation may shed further light on these survey results. Interestingly, many WLs who answered “No” to the question also provided comments such as the following along with their responses:

You might find these figures surprisingly high or low, or they might align exactly with your expectations. Regardless, one important data observation may shed further light on these survey results. Interestingly, many WLs who answered “No” to the question also provided comments such as the following along with their responses:

“We have a very healthy, active, and engaged worship culture. I love what the Lord has given us to cultivate and grow in our church community.”

“Most participants and curious onlookers would think our worship sounds similar to those listed.”

“Our style is already like that.”

This helps reframe our interpretation of the survey responses. Initially, we might assume that all “No” answers reflected a negative perception of the prominent worship cultures/styles. However, a closer look at respondents’ comments indicated that these responses may also signal WLs who believed their local church already aligned well with more prominent churches.

Of course, some respondents who indicated either “No” or “Sometimes” also emphasized the importance of their worship practices reflecting the unique culture of their own congregation:

“Why would we imitate another church? I am concerned about getting our specific congregation to sing, not someone else’s.”

“I’d rather see more churches adapt an expression more organic to their local congregations rather than feel pressured (or just adopt) trying to mimic industry recordings.”

“We aren’t those churches. We want to be us.”

While it’s understandable for WLs to desire a worship culture that closely aligns with their local church’s identity, the limited scope of our survey prevented us from determining exactly how these cultures are defined—be it through demographic traits of the congregation or specific geographical characteristics—or what motivates these preferences—be it theological beliefs or a practical emphasis on gospel relevance. Regardless, this quest for a genuine worship expression emerged as a prominent theme in the responses, highlighting the universal desire for “expression” as illustrated by the following:

“Only with the outward expression of worship that these churches have. It’s hard to sing to a congregation that looks like zombies.”

“Some Sundays I wish our congregation would have the energy of some of these churches. There are some Sundays where the congregation just seems dead or unenergized.”

“…I love how much people move and physically get into worship at places like Bethel and Elevation. Our people tend to stand and raise their hands and sing and that’s about it. Not much movement.”

“Sometimes I wish the church would ‘let go’ and just worship as you see like these artists/churches…”

When WLs interact with the audio/video recordings of prominent church’s songs, the energy, passion, and overall “vibe” from these bands and congregations make these songs more appealing for use in their own local churches. This “packaging” of the song can significantly influence a song’s adoption, something akin to what advertisers call “aspirational brand marketing”. In the right light, it would be easy to interpret some of the comments in our survey to indicate WLs may believe that incorporating these songs will replicate the seen and heard effects in their congregations. That is, by leading these songs they may become that kind of WL, and their congregation may become that kind of congregation.

Such marketing dynamics may be subconscious and undetected, even while being impactful. Theories like symbolic consumption and social identity theory offer insights into the underlying motivations driving WLs to choose these songs, suggesting that these decisions are influenced by more than just the music itself.

Of course, it’s not the case that every WL is entirely content with leading these songs:

“The church I’m in likes to use music from the artists previously mentioned but does not have the same kind of approach to worship that birthed that sort of music. To me, there’s a disconnect there — so it’s not so much that I desire that culture/style as much as I desire some cohesiveness between the kind of music that fits the understanding of worship the church has.”

Ultimately, our survey research revealed most WLs at least occasionally yearn for their local church’s worship “culture” / “style” to mirror that of the leading worship brands, especially in their “expressiveness”. This aspiration helps explain the widespread trend of unaffiliated churches (across denominations, demographics, geographies, and cultures) looking and sounding more like the Big 4 — showing that the influence of these brands (like the appeal of “energy”) is nearly universal.